Virtual Bakery Game Serves Up Both Cupcakes and Quantum Concepts For K-12 Students

When thinking about how to propel the field of quantum computing into the future, animated cupcakes might not be the first thing that comes to mind. However, a group of researchers at the University of Chicago might ask you to think again.

Quantum computing is considered a rapidly-growing field throughout the world that intersects computer science, physics, and math to solve a number of problems that classical computers cannot. The concepts grounding how it works are often abstract and may seem not only counterintuitive to someone without an advanced degree, but also intimidating to try and learn. Unfortunately this has the potential to limit the future workforce in quantum computing if it doesn’t become more accessible.

For researchers Tianle Liu, David Gonzalez-Maldonado, Danielle Harlow (Professor, UC Santa Barbara), Emily Edwards (Director of IQUIST, UIUC), and University of Chicago Associate Professor Diana Franklin, targeting students early before they lose confidence in the ability to understand quantum seems necessary to ensure we can continue growing the field. Naturally, one of the biggest challenges in doing so is finding a way to make quantum engaging to this demographic.

In research funded by the National Science Foundation, the team detailed Qupcakery; a unique food-style video game they created that introduces quantum gates to young learners through bakery roleplay. Qupcakery is part of Quander, a suite of games inspired by quantum concepts. The research was presented at Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education hosted by the ACM Special Interest Group on Computer Science Education (SIGCSE).

“Our game touches upon many quantum concepts – superposition, measurement, quantum gates, and even entanglement,” said UChicago graduate, Tianle Liu. “This is very uncommon to see within the same game context – because it is very hard to capture them all.”

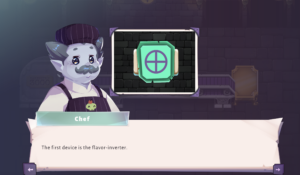

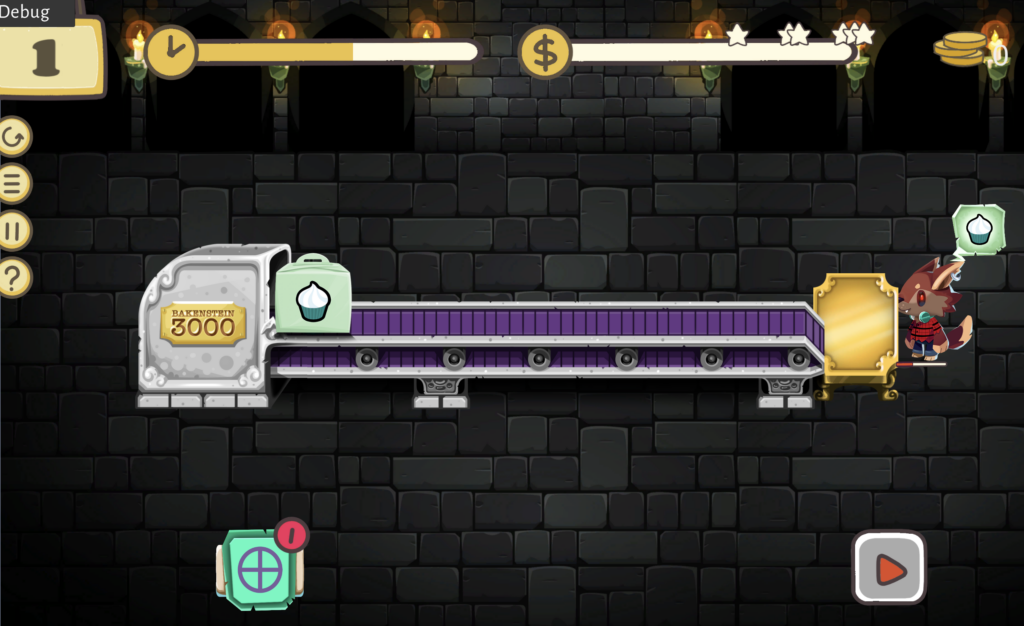

Players help an absent-minded cupcake chef serve vanilla (0 qubit) or chocolate (1 qubit) cupcakes to customers via conveyor belts. As the chef gets busier, sometimes he sends the wrong flavor cupcake down the conveyor belt and players must use quantum bakery devices (e.g. NOT, SWAP, and Controlled-NOT gates) to transform the cupcake into the correct flavor. They also might get a mystery box where the flavor is unknown, signifying it is in superposition. Customers line up with their cupcake orders, and players must arrange the gates on the conveyor belt in the right order to solve that level’s puzzle. If they aren’t able to solve the puzzle correctly or within the time constraints, customers leave upset and students won’t earn any coins.

Players help an absent-minded cupcake chef serve vanilla (0 qubit) or chocolate (1 qubit) cupcakes to customers via conveyor belts. As the chef gets busier, sometimes he sends the wrong flavor cupcake down the conveyor belt and players must use quantum bakery devices (e.g. NOT, SWAP, and Controlled-NOT gates) to transform the cupcake into the correct flavor. They also might get a mystery box where the flavor is unknown, signifying it is in superposition. Customers line up with their cupcake orders, and players must arrange the gates on the conveyor belt in the right order to solve that level’s puzzle. If they aren’t able to solve the puzzle correctly or within the time constraints, customers leave upset and students won’t earn any coins.

“It was very challenging to design game images and mechanics that made sense within the bakery setting while maintaining an analogy that matched the concepts as faithfully as possible,” said UChicago Prof. Diana Franklin. “We wanted an engaging game but did not want to accidentally introduce misconceptions that might haunt students if they later pursued quantum courses. Resolving such issues resulted in several extended discussions among the entire tri-institutional team.”

“It was very challenging to design game images and mechanics that made sense within the bakery setting while maintaining an analogy that matched the concepts as faithfully as possible,” said UChicago Prof. Diana Franklin. “We wanted an engaging game but did not want to accidentally introduce misconceptions that might haunt students if they later pursued quantum courses. Resolving such issues resulted in several extended discussions among the entire tri-institutional team.”

The 27 levels progress in complexity through the gradual introduction of new gates and concepts. If a student hopes to pass higher levels, they will need to remember previously introduced gates. The game scaffolds the more abstract math concepts in hopes that quantum will seem more accessible to students when it’s re-introduced later in life.

“From a self-advocacy standpoint, we want to introduce quantum to kids at a young age,” said second-year UChicago PhD student, David Gonzalez-Maldonado. “Research shows that by middle school, students have already made up their minds about what they are good at and what career paths they want to follow. So if you want to change the trajectory, you have to do it pretty young. Hopefully they will think back to fifth grade when they worked on the game and remember it wasn’t an outrageously difficult concept.”

During testing sessions for middle school and high school students, the research team collected both qualitative and quantitative data to determine effectiveness. Overall, most students thought the game was fun, and it sparked high schoolers’ interest in learning more about quantum computing.

During testing sessions for middle school and high school students, the research team collected both qualitative and quantitative data to determine effectiveness. Overall, most students thought the game was fun, and it sparked high schoolers’ interest in learning more about quantum computing.

“I was surprised how quickly some of the middle school kids grasped onto the quantum ideas,” said Liu. “In focus groups, some students were really quick to make the connection between superposition and the mystery qupcake boxes. This convinced me that young students are capable of understanding quantum ideas if we provide them in an accessible format.”

The few high-quality educational resources currently available on quantum are being aimed at undergraduate or graduate students with an existing background in computer science, physics, and math. Aside from creating a general lack of exposure for younger audiences, this also perpetuates existing representational problems; something the research team is passionate about addressing.

“Math, CS, and physics already have extensive research showing gender gaps,” said Gonzalez-Maldonado. “We’ve seen how problematic and how difficult it can be to achieve equity once a field fully matures. But we have this unique opportunity where quantum is still at a very early stage of development. Maybe if we can make a suite of games that can be widely disseminated so that anyone can access it, then maybe we can start bridging that representational gap in quantum before it ever gets the chance to develop. ”

The team will continue conducting research on Qupcakery through field studies and the addition of learning content. They hope to find that middle school students find the game well-paced and that some students are able to make connections without external intervention. To learn more about the research being done in this field, visit University of Chicago’s Computing for Anyone (Canon) Lab.