UChicago Scientists Develop New Tool to Protect Artists from AI Mimicry

Last year, the arrival of powerful AI models capable of generating original images based on text descriptions amazed people with their uncanny ability to simulate different artistic styles. But for artists, that wonder was a nightmare, with the easy, startlingly accurate mimicry threatening their livelihood.

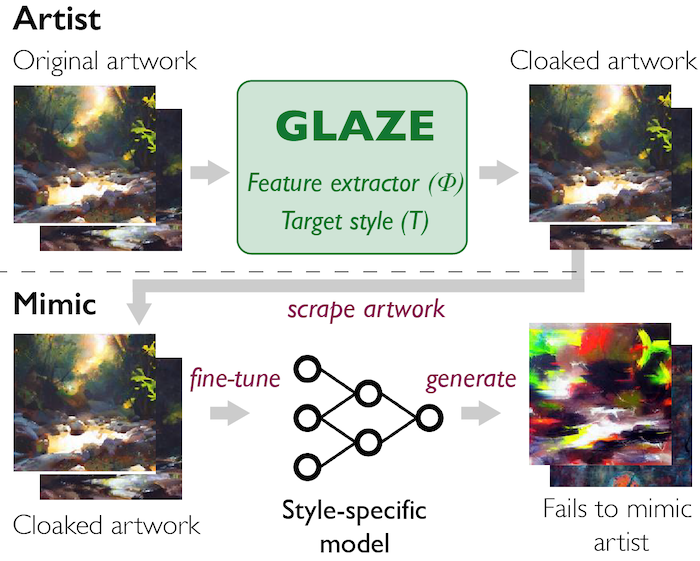

Now, a team of University of Chicago computer scientists have built a tool that protects artists from the absorption of their style into these AI models. Called Glaze, the software “cloaks” images so that models incorrectly learn the unique features that define an artist’s style, thwarting subsequent efforts to generate artificial plagiarisms.

[Read a New York Times story about Glaze and the technical and legal battles over generative AI art, and watch Prof. Ben Zhao discuss the work on WTTW’s Chicago Tonight.]

The research, developed by the SAND Lab research group led by Neubauer Professors of Computer Science Ben Zhao and Heather Zheng, gives artists a countermeasure against generative art platforms such as DALL-E, Midjourney, and Stable Diffusion, which have exploded in popularity. The team also includes UChicago CS PhD students Jenna Cryan, Shawn Shan, and Emily Wenger and assistant professor Rana Hanocka.

“Artists really need this tool; the emotional impact and financial impact of this technology on them is really quite real,” Zhao said. “We talked to teachers who were seeing students drop out of their class because they thought there was no hope for the industry, and professional artists who are seeing their style ripped off left and right.”

In 2020, SAND Lab developed Fawkes, an algorithm for cloaking personal photographs so that they could not be used to train facial recognition models. The research was covered by the New York Times and dozens of international outlets, and the software received nearly one million downloads. So when DALL-E and similar applications broke out last fall, SAND Lab started receiving messages from artists hoping that Fawkes could be used to protect their work.

However, merely adapting Fawkes for artistic images proved insufficient. Faces have a small number of features, such as eye color or nose shape, that models use to make their identifications, and slightly perturbing these features is an effective protection. But an artist’s style can be defined by a large number of characteristics, such as brushstroke, color palette, shadowing, or texture. To effectively cloak an artist’s work, the most important features that make up their unique style would have to be determined.

“We don’t need to change all the information in the picture to protect artists, we only need to change the style features,” Shan said. “So we had to devise a way where you basically separate out the stylistic features from the image from the object, and only try to disrupt the style feature using the cloak.”

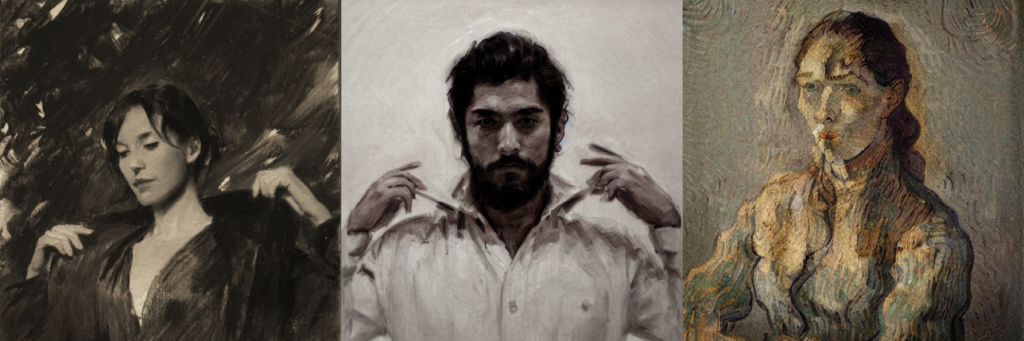

As a solution, the researchers hit upon the clever idea of using AI against itself. “Style transfer” algorithms, a close relative of generative art models, take an existing image – a portrait, a still life, or a landscape – and recreate it in a particular mode, such as cubism, watercolor, or in the style of well-known artists such as Rembrandt or Van Gogh, without changing the content.

Glaze works by running this process on original art, identifying the specific features that change when the image is transformed into another style. Then it returns to the source and perturbs those features just enough to fool art-mimicking AI models, while leaving the original art almost unchanged to the naked eye.

“We’re letting the model teach us which portions of an image pertain the most to style, and then we’re using that information to come back to attack the model and mislead it into recognizing a different style from what the art actually uses,” Zhao said.

When generative art AI systems were fed with the cloaked images, then asked to produce new images in the artist’s style, it returned much less successful forgeries with a style somewhere between the original and the style transfer target. Even when the model was trained on a combination of cloaked and uncloaked images, its mimicry was far less accurate on new prompts.

That’s good news for artists concerned that AI models have already learned enough from their previously published work to conduct accurate forgeries. Because these models must constantly scrape websites for new data, an increase in cloaked images will eventually poison their ability to recreate an artist’s style, Zhao said. The researchers are working on a downloadable version of the software that will allow artists to cloak images in minutes on a home computer before posting their work online.

The research team collaborated with artists at each step of Glaze development, first surveying over 1,000 professional and part-time artists on their concerns about AI art and how it would affect their career and willingness to post their art online. Glaze was tested on the work of four currently-working artists (as well as 195 historical artists), and a focus group of artists evaluated the software’s performance in disrupting AI mimicry. After viewing the results of Glaze cloaking, over 90 percent of artists said they were willing to use the software when posting their work.

“A majority of the artists we talked to had already taken actions against these models,” Shan said. “They started to take down their art or to only upload low resolution images, and these measures are bad for their career because that’s how they get jobs. With Glaze, the more you perturb the image, the better the protection. And when we asked artists what they were comfortable with, quite a few chose the highest level. They’re willing to tolerate large perturbations because of the devastating consequences if their styles are stolen.”

A preprint of the paper, “Protecting Artists from Style Mimicry by Text-to-Image Models,” is available now on arXiv, and you can read more about the project at the SANDLab website.